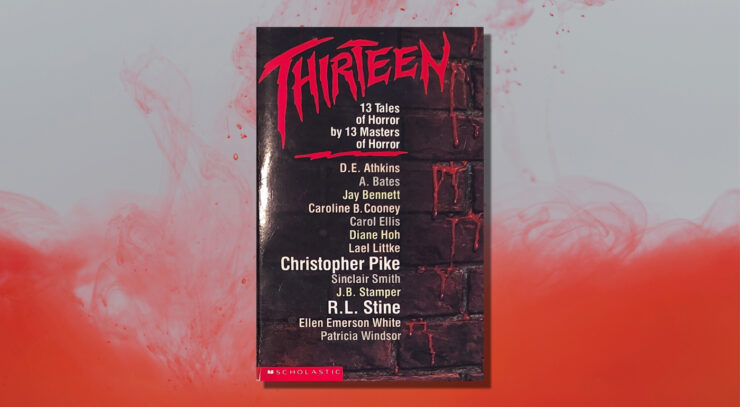

Teen horror of the ‘90s was dominated by familiar names like Chrisopher Pike and R.L. Stine, and extended series like Stine’s Fear Street and Diane Hoh’s Nightmare Hall. With the popularity and sheer volume of work being published, it is interesting that ‘90s teen horror was almost exclusively a long-form phenomenon: a few series, lots of standalone novels, but very little short fiction. Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series (1981-1991) and J.B. Stamper’s Tales for the Midnight Hour series (1977-1991) are both short fiction collections that likely appealed to ‘90s teen horror readers in their younger years and serve as notable predecessors, but they are separate from the larger ‘90s teen horror trend. Christopher Pike published two short story collections of his work—Tales of Terror (1996) and Tales of Terror 2 (1997)—though they never achieved the mainstream popularity of his novels. When it comes to ‘90s teen horror short fiction, the T. Pines-edited Thirteen: 13 Tales of Horror by 13 Masters of Horror pretty much stands alone.

Published by Scholastic, Thirteen features several familiar Point Horror names, including D.E. Athkins, A. Bates, Caroline B. Cooney, Carol Ellis, Diane Hoh, Lael Littke, and Sinclair Smith, along with those stars of the ‘90s horror firmament, Christopher Pike and R.L. Stine. The collection also features a handful of authors with whom readers might be less familiar, though their voices are quite in tune with larger tradition, including Jay Bennett, J.B. Stamper, Ellen Emerson White, and Patricia Windsor. In addition to showcasing a range of authors, Thirteen also serves to highlight the different horror traditions within the ‘90s teen subgenre: there are plenty of ghoulies and ghosties, from traditional vampires and ghosts to revenge-driven swamp goo, but there are also loads of real life horrors and one particularly memorable tale of cosmic ecohorror. Some of the stories are dark and nihilistic, while others champion the redeeming power of kindness and love. But all thirteen of these tales center around the lives and fears of their teen protagonists, as they try to make sense of and survive the worlds in which they find themselves.

Storytelling in the short fiction format is quite different from writing a novel. There’s a lot less time to develop the world and the characters, a lot less narrative space for twists and turns, red herrings and cliffhangers. Every detail carries extra weight, a freight of meaning and significance. This compression and intensity often contribute to a singular overwhelming tone or emotion for each short story, a feeling that readers might find hard to shake long after finishing the tale’s final line. That was certainly the case for me as I reread Thirteen for the first time in a couple of decades—there wasn’t a single story in the book that I could recall in narrative detail after all that time away, but there were some, like Windsor’s “A Little Taste of Death,” that elicited a strong emotional memory from their very first words, the echo of a feeling through the years rather than the recollection of the story itself. These stories are condensed standalone horrors, brief but powerful, telling their tales while drawing on and reflecting the larger horror traditions within which they were situated in the unique ‘90s horror teen landscape.

Buy the Book

Camp Damascus

Several of the stories are based in scenarios of real-life horror, dark secrets lurking just beyond the veneer of civilized society, or at least the often faux niceties and social complexities of young adult existence. For example, Jay Bennett’s “The Guiccioli Miniature” has the potential to be a cursed object story: while traveling in Venice, the main character, Jerry, buys a beautiful miniature from a down on his luck stranger, an exquisitely painted piece that the stranger says is a detailed copy of the miniature of Teresa Guiccioli, which is displayed in the Pitti Palace in Florence. Jerry buys the miniature—the price really is a steal—but immediately gets an ominous feeling, as he senses a shadowy figure following him back to his hostel, hears strange noises outside the door of his room, and sees his doorknob stealthily beginning to turn. Driven to terror and unnerved by Guiccioli’s image, Jerry screams and throws the miniature into the canal outside his room. After disposing of the miniature, Jerry sleeps a little more easily before reading the next day’s newspaper to find out that the miniature-peddling stranger was a thief who had double-crossed his partners, the miniature was the real deal and stolen, and the stranger’s angry partners were bent on getting the miniature back by any means necessary. Nothing overtly horrific happens to Jerry, though he clearly came within a hair’s breadth of violence, his well-ordered world nearly destroyed by a chance encounter.

Ellen Emerson White’s “The Boy Next Door” takes another approach to real-life horror by making the familiar terrifying: Dorothy is working a quiet shift at the local ice cream parlor and just getting ready to close up when Matt, a boy she knows from school, comes in. Matt seems a bit jittery, but Dorothy doesn’t immediately recognize any danger until he confesses to her that “I’ve always wondered what it would be like—you know, to kill someone—so I’m going to do it. Find out” (290). He has no real motivation for murder: he’s not in danger or desperation, it’s not a crime of passion or necessity. He’s just seen it on TV and in the movies, and wants to know what it would feel like to take someone’s life. As a result, there’s no real way for Dorothy to talk Matt out of it, no logical argument that would hold water in his likely sociopathic brain. In the end, Dorothy’s only way out is to spin a tale about how she actually has killed someone—their mean elementary school teacher Mrs. Creighton, who recently died in a car accident—and how it really wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, telling him “it doesn’t change anything. You do it, and you don’t feel better, you just feel—nothing … it’s a waste. You risk so much and you don’t get anything back” (294). He’s intrigued but unconvinced, until she offers to teach him and kill with him. A twist to this horror is revealed when Dorothy finally wraps up this nightmare shift at the ice cream shop, goes to watch the end of the Miss America pageant with her best friend Jill, then casually tells her that “We have to do it again … This will be the last one” (303, emphasis original). Jill is exasperated and vaguely interested, but decides that Dorothy’s explanation can at least wait until the next commercial break, a trifling nuisance in an otherwise apparently unremarkable conversation.

Other short stories in the collection blur the lines between real-life horror and the supernatural, hybrid terrors in which the characters often need to be just as frightened of themselves as they are of the monsters that stalk them. Christopher Pike’s novella-length “Collect Call” is divided into two parts, which bookend the collection. There are plenty of supernatural scares throughout the story, including a cassette tape of a supposedly cursed song, ghostly voices, and answering machine messages from beyond the grave. While these things are spooky, however, the story’s two young female protagonists, Janice and Caroline, are capable of significant horrors of their own. The two girls are both interested in mysterious Bobby Walker (maker of the cursed mixtape) and after a party, Janice agrees to drive Caroline home, even though Janice knows she has had too much to drink. They drive off a cliff, Caroline is killed in the accident, Janice attempts to stage the wreckage so that it looks like Caroline was driving, and when the car explodes and catches on fire, it turns out that Caroline wasn’t dead after all, just unconscious, as she is now burned alive. Her screams eventually die off, though when Janice gets home, she finds she has messages from Caroline on her answering machine, asking Janice to pick her up and give her a ride. When Janice returns to the scene of the crime, she discovers that she’s the one who was killed in the accident and Caroline survived. When she gets home, she discovers an answering machine message from Janice waiting for her. Janice tells Caroline: “don’t bother calling me back. I can’t answer the phone. The fire burned off my hands. But don’t worry, I’ll be in touch … soon” (48). In the second half of the story, Caroline finally goes out on her coveted date with Bobby Walker, who turns out to be a real weirdo—his idea of a good time is to take Caroline to the cemetery, dig up Janice’s grave, and bury Caroline alive with the other girl’s remains. Bobby ties Caroline up as he unearths Janice’s coffin, but she is able to make a daring escape abetted by Janice’s ghost voice and “Silent Night” (well, the first verse of the song at least), which Caroline clandestinely records over the cursed mixtape, diluting its dark power. This standoff ends with Bobby in the coffin rather than Caroline as she frees herself and tips him in, then maintains her calm composure fairly effectively as she shovels the dirt in to drown out his screams.

Patricia Windsor’s “A Little Taste of Death” and Diane Hoh’s “Dedicated to the One I Love” similarly blur the lines between human and supernatural horrors. The main characters in both of these stories do really terrible things. While Louey in “A Little Taste of Death” can blame her heinous actions on a supernatural influence that drives her to evil, in Hoh’s story, the supernatural becomes a means of revenge, the echo and aftermath of three young women’s acts of violence and secrecy. In “A Little Taste of Death,” kind, mild-mannered Louey suddenly becomes angry and cruel; she does terrible things while she’s asleep, including murdering a stray dog, as well as some undefined horror behind the closed living room door, which smelled “sickly sweet, and some undercurrent of the unmentionable; smells that shouldn’t be in living rooms” (117). Louey finds herself drawn into a vast conspiracy in which the devil in disguise tempts children with lollipops, which turn out to contain a unique poison that drives those who eat them to inexplicable violence ten years later. She meets others like herself, who ate their lollipops and who now find themselves doing things they can’t live with. However, after her isolated bouts of violence, Louey has apparently flushed it all from her system and can return to a normal teenage life because she only had “one good lick” (125) of the lollipop before her mother took it away and punished her (though it’s a bit hard to believe that she’ll be able to shake the horrifying repressed memories of the terrible things she has done so easily, and it sure as heck doesn’t help that poor dog).

In Hoh’s “Dedicated to the One I Love,” three best friends are driven into a jealous rage when they discover they’ve all been dating the same guy. When Marla, Carrie, and Lee discover that none of them are Richie’s one and only, they set out to play a prank on him, intending to drive him out to a local swamp, push him out of the car, and leave him stranded there … which works, right up until they realize that in speeding off, they shut Richie’s tie in the car door, accidentally strangling and dragging him. When they discover Richie’s mangled dead body, their solution is to roll him into the gray-green sludge of the nearby swamp and get on with their lives. They’re working pretty hard at keeping their dark secret and putting it all behind them when they start to hear mysterious dedications on the radio: first, someone calls in Richie and Carrie’s special song, “You Turn Me On,” then Carrie is killed when her radio falls into the bathtub. Richie and Lee’s song was “Falling For You,” which is requested and played not long before Lee takes a bad fall down the stairs and is paralyzed. Finally, Richie and Marla’s song was “A Knife in My Heart” and sure enough, that’s exactly what happens to Marla. Each of these murders is complicated by the fact that no one else hears these dedicated songs on the radio—not even the DJ who supposedly plays them—and each girl’s death is heralded by the oozing infiltration of noxious gray-green swamp sludge.

Finally, Thirteen features several stories that center around supernatural monstrosities, including D.E. Athkins’ “Blood Kiss,” Carol Ellis’s “The Doll,” and Caroline Cooney’s “Where the Deer Are.” Athkins’ “Blood Kiss” is an interesting riff on the traditional vampire story, tracking the experiences and responses of several teenage girls who think one of their mysterious male classmates Ken is a vampire. Val thinks vampires are sexy and Elizabeth becomes obsessed with Ken, while Delia is the voice of reason, telling her friends “If he were a real, live vampire, it would be life-threatening … Because he would put his teeth into your neck and suck out your blood, and you’d be dead” (87). Despite their range of responses, however, they all end up going out with him at least a few times. Honestly, “Blood Kiss” is at its most unnerving when vampirism is symbolically engaged: girls go out with Ken, he does something horrible to them that they won’t talk about, and they’re depressed and withdrawn afterwards. If we don’t believe in vampires, these are pretty clear warning signs of relationship violence and sexual assault, and the story loses some of its depth and resonance when it turns out he’s a vampire … but so is Elizabeth. Ellis’s “The Doll” has the feel of an old-school Victorian-style ghost story, with a frame narrative of a man who discovers a box holding a vintage porcelain doll along a rocky coast. The rest of the story is an extended flashback, as Abby Rogers finds the same doll in the house into which her family has just moved, and the doll begins to wreak havoc on Abby and her family. Like Louey in “A Little Taste of Death,” Abby’s first sense of these dangers comes through her dreams, when she sees tiny pale hands inflicting violence: pushing her friend Erin down the stairs, unscrewing a chandelier to fall on her friend Holly’s head, lighting the match that sets fire to her little sister Lindsay’s treehouse. Abby doesn’t put two and two together until she has a dream about Mark, the boy she’s excited to go on a date with, and sees the doll’s tiny form and old-fashioned dress stepping out in front of his car, causing him to swerve into the accident that kills him. In the end, Abby can’t destroy the evil doll—all she can do is chuck it over the edge of a cliff to the rocks below and hope for the best. However, an unnamed man finds the box and is thrilled to discover the doll inside, a perfect Christmas present for his daughter, the promise of more horrors to come.

Caroline Cooney’s “Where the Deer Are” is in its own class of the supernatural horrors of the larger collection, an unnerving and slightly trippy tale of cosmic ecohorror that explores the permeability between dimensions and the revenge of the natural world. Like “Blood Kiss,” the horror in “Where the Deer Are” starts out feeling like it could be explained through rational means: there’s a stretch of road going past the woods that a group of children walk along to get to and from school, and a couple of decades ago, two children went missing there. It has the usual trappings of urban legend, passed along from one generation of children to the next, though despite the genuine spookiness surrounding the story, there’s a very real possibility that the children were kidnapped or ran away from home. That doesn’t make the walk any less unnerving for Tiffany and her friends. The woods are well populated with deer, though Tiffany notes that the deer look mangy and a bit flat, what she refers to as “deer-oids” (168). She sees them as creatures, not properly alive, and when her dad hits a deer with his car, she looks at the dead animal and thinks of it as “unchanged, looking just as alive, and just as not-alive, as before” (168). This dissonance between human and nature—and the human lack of empathy for either—is further emphasized in the state of the woods themselves, which are littered with “discarded hamburger wrappers, old liquor bottles, pieces of newspaper, and strips of tires. You had to look over the trash to see the woods, and as deep in as you looked, the woods was not pristine forest, but full of junk” (173-174). One day on the way to school, Tiffany and her friends get the unsettling feeling that something is watching them, that something is about to happen, that “Today is the day the cliff chooses” (175) which of the children it will take next. Tiffany gets separated from her friends and when she runs into the school, she finds herself still mired in a liminal space, separated from both the wilderness and the civilized safety promised by the school building, which is ominously empty. When Tiffany goes into the girls’ restroom to gather her wits, she looks into the mirror and instead of her own face, sees that of a deer staring back at her, before the deer starts to emerge from the surface of the mirror itself, “First one deer leg, thin as a broken pencil, then the next” (179), as Tiffany’s perceptions continue to emphasize the not-alive nature of the deer. When Tiffany flees back to the forest, all of these worlds collide, as liminality collapses into hybridity and Tiffany sees the world through a complex prism as “For a moment, she was all of it: hunter, hunted, and remains” (181). Though Tiffany can see her friends in the distance—they even see and wave back at her—she can never escape this hybridity, will never make it back to that world. A door opens beneath her and scrambles her entire sense of what the world is and how it works, as “Tiffany saw the laughing deer, the sneering underside of the road, the strangling vines above the ground and beneath the soil. The trees closed around her, like shovels full of dirt on a coffin … Tiffany began the long fall. She knew the fall would never end” (182). In her final moments in this plane of existence, Tiffany claims innocence, that she is not the one who cut down the forest for housing developments, that she is not the one who was driving the car that hit the deer, though her disregard for the alive-ness of the deer themselves and her apathy about the garbage dumped in the forest are perhaps a microcosmic echo of these larger abuses. The children’s compromised relationship with and lack of consideration for the natural world are clearly addressed in the story’s final lines, as one of Tiffany’s friends “finished the soda he had taken from the lunch bag his mother had carefully packed. He threw the can into the woods … It glittered, scarlet and silver, like a marker on a grave” (182), one more piece of trash in an already ruined wilderness.

The stories featured in Thirteen provide a fascinating snapshot of the key themes and trends of ‘90s teen horror. The authors take different approaches to their horrors, from the realistic to the supernatural, and somewhere in between, with the collection showcasing the range of the genre. However, despite their different approaches to the horror itself, there are several common anxieties and concerns that radiate through the collection as a whole: desire for a sense of belonging and acceptance, the fear of being misunderstood, these teens’ concerns about how they fit into (or fail to fit into) the larger world around them, the terrifying realization that their actions may have consequences they never intended, that they are capable of making mistakes that can’t be undone or set right, no matter how sorry they may be. For these young protagonists—and young readers—they are coming to realize their own power and their own impact on the world around them, which is simultaneously thrilling and terrifying. They are making and shaping the worlds around them, but sometimes, those worlds are full of nightmares.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.